This article is also available in French

Foreword

One man above all has kept the memory and achievements of the French pioneer of modern catamarans, Eric de Bisschop, alive. This is James Wharram, who in 1944, at the age of 16 bought the English translation of Eric de Bisschop's book 'The voyage of the Kaimiloa' (published in English in 1940).

The voyage of the KonTiki raft, in 1948, to prove the theory of the settlement of the Central Pacific islands from South America (East-to-West theory), achieved worldwide fame for Thor Heyerdahl.

In contrast, because of the post war political situation in France, Eric de Bisschop's pioneering voyage from Hawaii to France on 'Kaimiloa' in 1937-39, proving the seaworthiness of the raft stable double canoe, was forgotten.

James Wharram, with his cherished book 'The voyage of the Kaimiloa' took up the banner of Eric de Bisschop and between 1954 and 1959, in two pioneering double canoe voyages across the Atlantic, confirmed that Eric de Bisschop was correct in his assumption that the ancient Pacific raft-stable double canoe enabled ancient Pacific migrations to have been made from West to East out of SE Asia.

The following 'first' major article about Eric de Bisschop was written by James Wharram in 2004 for the French yacht magazine Chasse Marée. Unfortunately is was never published in France, but was printed (without permission) in the Newsletter of the Junkrig Association in August 2005.

In February and March 2012, another French yacht magazine, Voiles & Voiliers, were the first to publish two in-depth articles on the voyages of Eric de Bisschop, which shows that the yachting public is finally becoming aware of the pioneering sailing achievements of this long forgotten French sailing hero.

Voiles & Voiliers acknowledge James Wharram as the man who followed in Eric de Bisschop's wake and as a result became a leading designer of present-day catamarans.

As advocate of Eric de Bisschop, in 2007 Wharram protested at the publication of the book 'Vaka Moana' in New Zealand, that destructively minimised Eric de Bisschop's achievements in Pacific migration studies. Then in April 2008, in a paper given by James Wharram at a Marine Archaeological Conference at the KonTiki Museum in Oslo, he was at last able to establish the pre-eminence of Eric de Bisschop in Pacific maritime studies.

For more than 70 years Eric de Bisschop's sailing achievements have stayed in the shadows. It is time everyone with an interest in the history of multihulls knows more about him.

Eric De Bisschop

It is time to draw attention to France's great sailing hero of the 20th century, Eric De Bisschop.

A flying ace from the First World War during which he received the Croix de Guerre. Imprisoned in the 1930s by the Japanese on a Pacific Island as a spy. Imprisoned during the war by the Americans on Hawaii as a spy for the Japanese!

A man, whose voyages in the late 1930s aboard his Double Canoe proved the theories of Thor Heyerdahl wrong, before Heyerdahl even began his famous raft voyage!

A man, whose sailing companions, both men and women, were devoted to him. Yet, his many enemies conspired to write him out of history.

French sailing heroes have nearly always been more than just sailors. They tend to be awkward, difficult individuals moved by a deep personal philosophy derived from how they perceived the ocean.

Eric De Bisschop was the first in the 20th century of such great men. Above all, he was indisputably the first modern offshore double canoe/catamaran sailor in the western world. From his pioneering double canoe/catamaran voyage in the late 1930s on the 38ft Kaimiloa, all modern offshore catamarans descend.

I know this because 50 years ago, I was the first European to successfully sail a catamaran around the North Atlantic. At that time, I was inspired by Eric De Bisschop. When during these voyages I was being told in each port that my double canoe "could not sail to windward, that in gales waves would sweep across the decks, that these waves would smash the boat apart", I would read my Eric De Bisschop book "The Voyage of the Kaimiloa", and gain the courage to sail on.

Eric De Bisschop's book was published in Britain in 1940. I bought my copy at the age of 16 in 1944. "The Voyage of the Kaimiloa" was the first book of my present day library of several hundred books of the Sea and Boats.

It is written in a descriptive simple "stream of consciousness" style. It opens with Eric, a victim of severe starvation, reflecting in his bed in a leper hospital on a Hawaiian island, describing how he had arrived there.

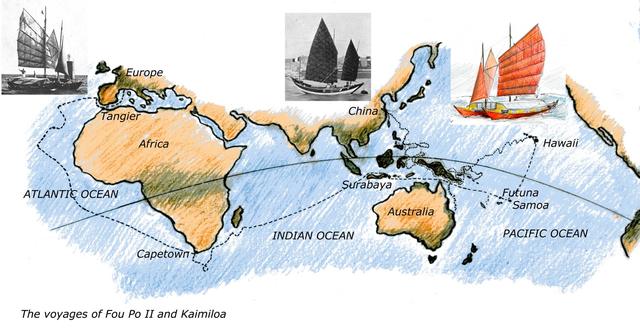

In the first eight pages, De Bisschop modestly delineates his two incredible small boat journeys that began in Shanghai, China in the early 1930s. The first on a 40 ton (approx. 60ft long) Chinese Ningpo Junk (Fou Po I) he built 1000 km up the Yangtze, before she was wrecked in a typhoon off Taiwan. Undaunted with his friend and yearlong crew Joseph Tatibouë t (a Breton) he returned to China and in 3 months built a smaller 40ft Junk.

De Bisschop's hospital bed reflections go on to describe how aboard this Junk, the Fou Po II, he and his friend sailed through the Philippines, the Dutch East Indies, Northern Australia, Papua New Guinea, Melanesia and then on to the atoll of Jaluit in the Marshall Islands, studying ocean currents and the possible migration routes of the people that had settled the central Pacific Islands.

In the 1930s the then militarist Japanese controlled the Marshall Islands. The Jaluit Governor knowing nothing about western sailing heroes promptly threw De Bisschop and Tatibouet in jail as spies. In those years, getting thrown into a Japanese jail on these Pacific Islands as a spy usually meant an unpleasant death!

Somehow De Bisschop talked their way to release and thankfully sailed out into the open sea for a 2500 mile voyage to Hawaii sailing against the trade winds and prevailing ocean currents. This voyage from Jaluit to Hawaii, in itself a major small boat voyage, was to be an extended one because De Bisschop was still determinately studying ocean currents. After 1½ months a bad smell in the food lockers revealed that the Japanese searching their ship (for evidence of their spying), had opened their sealed food containers so their basic stores had gone rotten. From then on it was a month of starvation until they reached the Hawaiian Islands. They managed to anchor off the leper colony of Kalaupapa and were carried into the hospital.

These two Frenchmen in the early 1930s, when very few Westerners had sailed the Oceans in small boats, and almost none had risked sailing them in a "native" boat (a 40ft Junk), had sailed over 10,000 miles against the prevailing winds and currents of the Pacific ocean. For this one reason alone they should be honoured as great small boat (French) sailors.

The hero story exists in all cultures of man. Inevitably, the hero survives one great test to be surprised by an even greater test. Eric De Bisschop received another blow from fate. In his hospital bed he noticed the nurses and doctors looking sad and worried. Then his crew Tatibouet came in the room clasping Eric in his arms, telling him that last night a storm broke loose the anchored Fou Po II and smashed her to pieces on the rocks.

Eric at first collapsed, then an old French missionary priest of the leper colony managed to comfort him. Then Tatibouet offered to build Eric a new Junk, to which Eric answered, "No, my good Tati, not a Junk this time; we are going to build – a Polynesian double canoe." "... it is a type of sailing-ship which Polynesians used in former days to cross the Pacific."

Next, he describes being flown to Honolulu, being greeted by an excited American press. How in 12 months in Honolulu he designed and built the 38ft double canoe/catamaran Kaimiloa, met and fell in love with a beautiful Hawaiian woman, Papaleaiaina, descendant of the last great maritime king of Hawaii, Kamehameha. Quite a romantic story.

50 years ago as a De Bisschop disciple, planning to sail the ocean with my own two beautiful women, I found these chapters most frustrating. I was not interested in "his" love story. I wanted to know precisely in detail how he had designed and built the first modern catamaran, not his philosophic ruminations.

Now with hindsight I realise, what De Bisschop was describing was not so much his double canoe design, but his head-on conflict with the "academics" of the Bernice P. Bishop Museum of Hawaii!

In the 1930s the sciences of anthropology, archaeology, ethnology, which relate to the study of man and his origins were only just developing. The new "scientists" emerging in these fields were not sure of themselves; very Kaimiloa SB lower hulloften they met with conflicting theories in the "outer world".

A great academic issue amongst these scientists was the origin of the people of the Central Pacific Islands. How did they arrive in these mid ocean islands? They certainly had not walked there, they had to have got there by some type of watercraft. If they came from the west, from Asia, sailing east they must have sailed for thousands of miles against the prevailing winds and currents, a route that Eric had sailed on his Fou Po II in his personal attempt to prove its possibility.

When the Europeans discovered the central Pacific Islands in the 18th century these experienced ocean sailors accepted the outrigger/double canoe craft they observed as seagoing craft. But by the 20th century under the influence of Missionaries and Colonial Administrators the same type of "Canoe Craft" were being described as "unable to sail to windward, that in bad weather waves would wash across the decks and the canoe structure would break up." Eric De Bisschop reveals that he entered into these Academic problems like a whirlwind.

In public lectures he was saying, "I have just spent 3 years sailing from SE Asia on a 40ft native craft, i.e. a Junk, studying the winds and currents on the route to Hawaii", showing it is possible for a native craft to sail against the wind and survive storms. (For which he had received the Charles Garnier Prize from the Société Française de Geographie, which gave him the funds to build the Kaimiloa.) Now he announced he was going to design and build a 38ft Ancient Double Canoe, the craft of the Central Pacific to carry on his Ocean Research.

Unfortunately, he also derided the canoe models exhibited in the respected Bishop Museum as "picturesque models manufactured to please the inquisitive tourist." What he did not seem to realize was that he had made bitter academic enemies that would help to write him out of Sailing History.

In retrospect it is easy to see why the love and support of Papaleaiaina, descendant of the last Hawaiian king, meant a great deal to him. She represented the spirit of the ancient Pacific.

On 11 October 1936, 12 months since De Bisschop had arrived in Hawaii, the Kaimiloa had her first trial sail. It was a success. The Chinese rudders gave perfect steerage, the bamboo battened Chinese sails gave drive and sail control. The combination of lashed rudders and sails gave the self-steering abilities, important to Eric. For he was insistent, as was Joshua Slocum, that ocean going small boats should be balanced under sail, rudder and hull to give self-steering. For the final test Eric headed for rough short choppy seas off Koko head. The two canoe hulls assembled into a raft shape rode, as Eric wrote, "smoothly and harmoniously". All seemed well.

The second test sail of the Kaimiloa was a month later. It was a disaster. The plan was to sail around the island of Oahu. Sailing clockwise, west, north, then northeast to the most northerly point, then southeast to complete the island circumnavigation.

The first day was good sailing but then as they rounded the island they began to head into strong headwinds, high short seas and, trouble.

All sailors make mistakes, even the great ones. Eric had failed to caulk his forward decks properly. Smashing into the head seas the bows were awash. The badly caulked decks leaked into the forward watertight compartments. The water rose in these compartments, the weight of the water sinking the bows low into the sea. Then the trapped water flooded through the uncaulked upper part of the bulkheads into the main cabin.

The solution, that only a sailor of Chinese Junks would know of, was to bore holes in the hullsides at the bows to let the water from the deck drain out rather than fill the forward bow compartments to flood over into the main cabin.

In 3 days' struggle around the windward side of the island the long suffering Tati either lost his nerve or was just fed up with Eric's ideas; he kicked his bailing bucket away and said, "let it sink". In the heart to heart talk that followed Eric agreed to give up his studies of sea currents and sail direct from Hawaii home to France.

"With joy", Eric tells us, "Tati resumed bailing", whilst Eric realised that in waiting for the right wind season to sail South, he could spend more time with his beloved Papaleaiaina.

Eric had planned to leave Hawaii quietly without fuss on the 7th March 1937. All sailors will know how he felt. Unfortunately, the American press got to know his plans, for they had been very interested in his liaison with Papaleaiaina, and hundreds of well wishers turned up to say goodbye. Eric was very concerned that he had not received official permission to fly the French flag. Even so, he defiantly hoisted the Tricolour.

Late in the day, having said farewell, he sailed into the open sea away from the crowds with about 2600 miles of open sea before him to reach his next landfall, the island of Futuna. Clear of the land Tati emerged on deck with an anguished face saying, "Captain, captain we have sprung a leak, we are going to sink".

The problem was the same deck leaks through bad caulking that had caused him problems 4 months before on his first major test voyage. Eric's excuse was that he hated to do work before dock on-lookers. I do not believe it. I just think that he was the skipper type that is unperceptive to minor discomfort. Another famous small boat sailor of this type was David Lewis.

In the first week of the voyage the weather was squally. With all sails up the Kaimiloa skipped along at 7 knots, but leaked. With the mainsail reefed Kaimiloa ambled along at 3 to 4 knots and no deck leaks. When the squalls hit the double canoe the Chinese Junk sail, as Eric enthusiastically wrote, was "reefed in minutes". The sea life routine that Eric loved became firmly established; he wrote, "Nothing to do but read, work and dream."

A look at the chart shows that Eric De Bisschop was making an epic voyage, navigating as he writes, with a "good sextant" and a "poor chronometer" sailing south across the equator to an atoll called Swains Island; then on to sight the summit peaks of Samoa, from there on to the lonely French island of Futuna, where he arrived on the 14th April 1937, 38 days after leaving Hawaii.

Eric spent 11 days on Futuna and devoted a chapter of his book describing the island and the people. It must be remembered that in 1937, talking to a 60 year old islander, meant you were talking to a person born in 1877, a person whose father and grandfather were in effect Ancient Polynesians. Eric modestly took his sailing skills for granted for he saw himself as a field ethnologist/anthropologist; a pity he did not write a separate book on his ethnological observations.

Eric and Tatibouet left Futuna on April 25th. Their course was close to the route of the famous captain Bligh's small boat voyage.

Around the 11th May they were sailing between the Santa Cruz and Banks Islands close to the island of Tikopia, where 60 years later I was sailing my Double Canoe to study the ancient canoe shapes of this tiny island settled by Polynesians.

4 weeks after leaving Futuna, Eric and Tati were approaching the Torres Straits between the most northern point of Australia and New Guinea. Passing through the Torres Straits means you have left the Pacific Ocean behind and entered into the Indian Ocean.

The problem is that to enter the Indian Ocean you have to cross the great Australian Barrier Reef. There are passes through the reef. I, with good charts, GPS, emergency engine power sailed through a Barrier Reef pass. It is awesome, with great ocean breakers beating down on either side of the passage.

De Bisschop had no engine, no GPS, his chronometer was untrustworthy for precise sextant navigation and he had only a small-scale ancient chart. His plan was to find Bligh Entrance, which he had come out of on Fou Po II.

They sight Murrey Island (40 M south of Bligh Entrance) behind a line of breakers. Rather than look for the main passage they spot a small break in the waves. Risking everything they sail in over the reef. A keel yacht would have struck with fatal disaster, but Kaimiloa with draft of just one meter survived! Even then, once through the breakers, Kaimiloa spent another hair raising 6 days in the shallows of the Barrier Reef before she made her way clear and sailed confidently into the Indian Ocean towards Bali.

Controlled by the Dutch in the 1930s, Bali was still a free Hindu kingdom; its women were famous for being beautiful and "topless". It had also then beautiful double outrigger canoes. In many aspects it was like Polynesia before the missionaries got there, a wonderful place for ethnographic/anthropological study or just plain joyous living.

While carefully noting currents Eric pressed on past Bali, like Odysseus passing the Sirens, to Surabaya, Java, where letters awaited him from Papaleaiaina!

He spent only a few days in Surabaya, still finding time to make comments on the sailing craft and racial characteristics of the people in relation to his arguments with the academics of the Bishop Museum.

By the 2nd July 1937, Eric records, "We have entered the great Indian Ocean, the volcanic cones of Java have disappeared beyond the horizon behind us. Ahead of us 3000 miles of water, plucky little Kaimiloa it is up to you."

Eric was steering a WSW course, 3000 miles to Reunion Island, which lies off Madagascar. Then with that fixed point heading on another 2500 miles to Cape Town, for the 1930s' small boat sailor a dramatic, pioneering, non stop voyage of nearly 6000 miles.

Eric records on this great voyage meeting whales, preparing food, political thoughts, but he was never bored. He records daily runs of 150 to 165 miles. Kaimiloa was making daily runs equal to a ballasted mono hull. Kaimiloa, as Hanneke's studies show, was built like a wooden fortress! Survival, not speed was Eric's design intent.

As Eric writes "...not bad for a wretched little double canoe derided at her conception, an illegitimate child without identity papers." (Interestingly, on my pioneering voyages I got angry at the snobbishness of the English. Lack of ship papers was unimportant to me.)

On the 18th August, 7 weeks after leaving Indonesia, Eric's navigation placed him 30 miles east of Port Elisabeth. To round the Cape to Cape Town, out of the Indian Ocean into the Atlantic was another 500 miles, some of the hardest sailing miles in the world. As August is winter in the southern latitudes Eric set a course south to clear the land.

As well he did, for within two days Kaimiloa was hit by a deadly winter storm. The forestay broke, a tiller broke leaving the heavy rudder slamming around. They tried out a sea anchor bought in Hawaii. It was useless. Then they hoisted a little triangular sail at the stern. The ship immediately lay better even though the seas were breaking on them from all sides.

Their estimated position was about 130 Nm south of Cape Agulhas. After 5 days the storm had blown itself out. Building the Kaimiloa like a wooden fortress had been a good idea. On that day they repaired and dried out the ship and sailed towards Cape Town. By the 27th August, they were beating their way into the Atlantic and Cape Town harbour.

Cape Town and its yachtsmen took the Kaimiloa and its crew into their hearts, but by 12th September the Kaimiloa was beginning her final ocean voyage of 6500 miles to the port of Tangier at the entrance of the home waters of Eric and Tati: the Mediterranean.

After the first week Eric wrote in his journal, "What grand sailing! On a boat like the Kaimiloa there is nothing to do except potter at anything that takes you fancy."

Kaimiloa passed the traditional Atlantic island sailing ports of St. Helena, Ascension Island and the Cape Verdes. It was a yachtsmen's dream sailing. Under these pleasant sailing conditions Eric informs us interestingly that he and Tati had their emotional differences. From my sailing experience this is understandable, the stresses had built up after years of hard sailing together.

Eric's sailing plan had been to call into Madeira, only to be met by easterly winds, which prevented a landfall. Instead he headed for the Azores. More head winds; so he sailed for Portugal, the river Tagus and Lisbon. More head winds. On his Pacific sailing ship Eric wondered if Magellan had upset the Pacific sea gods. Finally the 30th December 1937 on failing to enter Setubal, Portugal, Eric decided to head for French Tangier.

Hungry and thirsty, desperately short of food, completely run out of water, paraffin and cigarettes (2 buckets of hailstones in a squall kept them going), he and Tati carried on and safely reached Tangier on the 4th January 1938. It had taken them over 3 1/2 months non stop.

15 months after leaving Hawaii, having sailed nearly 19,000 sea miles across 3 oceans, Eric, Tati and the Kaimiloa were on French territory and nearly home; they took a rest.

The Kaimiloa and her crew spent 4 months in Tangier. Staying at the home of a First World War Comrade Francois Pierrefeu, Eric relaxing, writing his book and enjoying the company of his beautiful Papaleaiaina, who joined him there.

It was 14th May 1938 when the Kaimiloa left Tangier and a week later, she was sailing in French waters, Marseilles, Toulon to Cannes. French naval ships greeted Eric, Tati and the Kaimiloa with dipping flags and respect. At arrival at the port of Cannes a civil reception and national newspaper coverage awaited the crew of the Kaimiloa. Public lectures were arranged, and even a telegram from the First World War French hero Maréchal Pétain reading, "Bravo Eric, I am proud of you", signed Pétain. By 1939, Eric De Bisschop with the help of Tatibouet had achieved the National Hero status he deserved.

But by 1949, a war and ten years later, Eric De Bisschop was almost a forgotten figure. In 1949, some Frenchmen had built a 46ft double canoe catamaran in steel, the Copula, that made a most unpleasant voyage across the Atlantic, after which the craft was abandoned. In "The Voyage of the Copula" published in English in 1959, Jean Filloux gives a brief brush-off mention of De Bisschop's legendary voyage.

In 1947, Thor Heyerdahl sailed his 46ft balsa raft Kon Tiki 4000 miles downwind from Peru to the Tuamotos to prove his theory that central Polynesia was settled from Peru, using the favourable ocean winds and currents. The assumption behind Heyerdahl's theory was that the ancient Pacific double canoe could not have sailed to windward from SE Asia, carrying settlers because of inherent structural weakness. No academic from the Bishop Museum came forward to say that ten years earlier two Frenchmen had sailed a double canoe of Tuamotuan hull shape 19,000 miles to France.

In 1992, I was in Hawaii meeting Rudy Choy. Together with Woody Brown he built the first American offshore catamaran, with a hull shape based on Micronesian canoes. In the second half of the 1950s they sailed it from Hawaii to Los Angeles and back. He knew of and valued Eric De Bisschop. He told me Eric's wife Papaleaiaina was still alive in the islands. Unfortunately, I had no time to look for her.

Since the age of 16, inspired by Eric De Bisschop's book "The Voyage of the Kaimiloa" and guided by its subject to make a deep study of Pacific canoe form craft in British museums and libraries, I built in 1954 Britain's first offshore catamaran, the 23'6'' Tangaroa. In 1956, I was making Britain's first transatlantic multihull voyage from the Canaries to Trinidad. I had learned another thing from De Bisschop "no male crew", my crew was two German ladies!

Little did I know, as I was struggling across the Atlantic, that De Bisschop was at that very moment in the Pacific onboard a bamboo raft called the Tahiti Nui struggling from Tahiti to Peru; in an attempt, I believe, to re-establish his name as an ethnologist.

As a result of terrible storms his raft was damaged and got finally destroyed by a Chilean coast guard ship that came to the rescue.

A year later, with the help and encouragement of my friend Bernard Moitissier, I began building a 40ft double canoe, later to be the first multihull to cross the North Atlantic.

At the same time the indomitable Eric De Bisschop on a new raft, the Tahiti Nui II was struggling back from Peru to Tahiti. After 4 months, it began to sink. His crew built in the ocean a new smaller raft, the Tahiti Nui III, out of the more buoyant parts of the Tahiti Nui II.

On this voyage, at the age of 67, Eric became weaker and weaker. His crew caringly looked after him. One member of his crew was Bengt Danielson, one of the crew on Thor Heyerdahl's raft, who later wrote the book about this voyage ('From Raft to Raft'). Two weeks later they crash-landed Tahiti Nui III at night over the reef of the northern Cook atoll, Raka Hanga, Bengt and another crew member supporting Eric one on each side. It was reported he had a smile on his face. Washed off the raft in the waves Eric was rescued unconscious. Next morning he was discovered to be dead, still with a smile on his face.

It took many years before I learnt why perhaps Eric De Bisschop was ignored in post war France. The welcoming telegram from Maréchal Petain on arrival in Cannes in 1938 led to Eric during the war years being made French Consul in Hawaii, French Consul for the Vichy Government! After the war Vichy supporters had difficulties in France.

I know from my reading that Eric De Bisschop was a loyal French citizen. A great ocean sailor, he was the inspirer of the modern catamaran development. In modern strong France it is time to give him a place of honour amongst the great French Sailors of the 20th century.

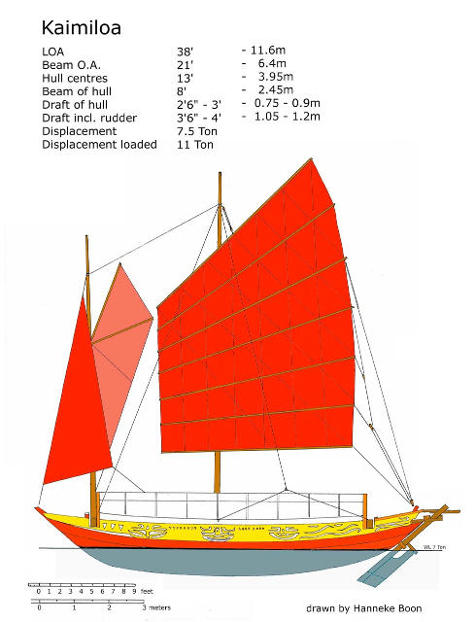

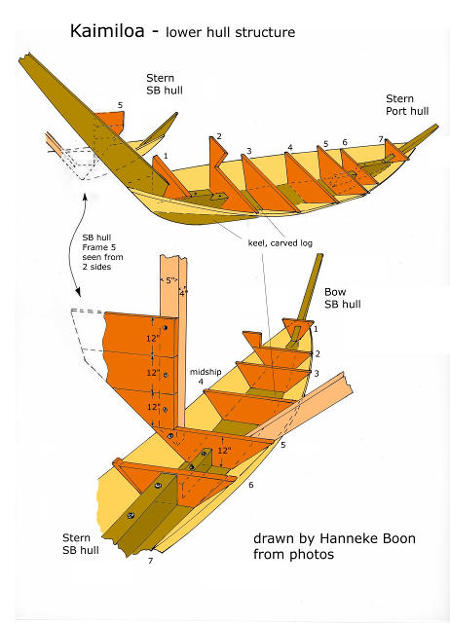

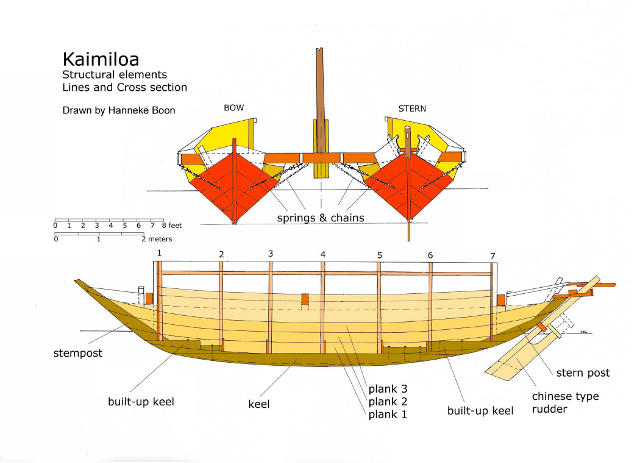

So, what did Kaimiloa look like and how was she built?

Unfortunately no drawings of Kaimiloa have ever been published. Besides some indistinct photos, Eric de Bisschop’s book only contains a few references to the design and construction of Kaimiloa:

"What shape am I to give the hulls?

"...instinctively I realise why Polynesian sailing craft of old like those of many islands of today, are shaped like half-moons with lines obviously as fine as possible on account of leeway, but with their submerged lines increasing the displacement...

"...it is not so very idiotic; to preserve the mode of construction of the Polynesians, who in their seagoing craft started from the initial principle of the dug-out, adding to it, in order to increase freeboard, as many planks as were necessary... I have discarded the usual keel; in its stead, a thick beam carved to shape, on the top of which we have nailed the planking of the hull."

There are a few more references to the joining of the hulls, rudders and sail rig, altogether not very detailed, but taken together with careful study of the few small photos and cross reference to drawings of Chinese junk sails and rudders I have been able to draw a fair reconstruction of the design and construction of Kaimiloa.

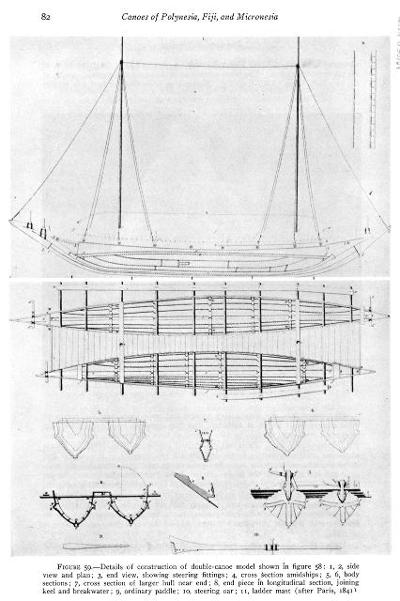

Eric did write that he had studied the reports of European explorers who mentioned Tuamotuan canoe builders. One of these was Admiral Paris, a Frenchman, who in 1840 recorded and had a model made of a Tuamotan voyaging canoe (both in the Louvre). Another model of such a canoe was in the Bishop Museum in 1936 when Eric was in Hawaii.

Kaimiloa bears great similarities to the Tuamotuan double canoe as can be seen when comparing my drawings of Kaimiloa to those of Paris. The cross-sections as well as the profile are almost identical, even the long cabin has the same proportions.

One intriguing coincidence is that in 1936, while de Bisschop was designing and building his double canoe, the Bishop Museum published the first volume of a book called ‘Canoes of Oceania’ by Haddon and Hornell, which included Admiral Paris’ drawing, model and descriptions. We think that perhaps Eric did view some of this material, but for political reasons failed to mention this in his book.